|

This talk lies at the intersection of my interests in technology and law.

|

|

First things first: I am not a lawyer. Please don't take anything I'm

about to say as legal advice.

|

|

So, when I say 'data', what am I talking about really? Am I talking about

big data? Small data?

People usually define 'data' as a collection of values for one or more

variables, or as discrete pieces of information.

|

|

Interestingly enough, the word 'data' is the plural of datum, which is a

Latin word meaning "(something) given"

|

|

Which brings me to a question: What kind of data is worth protecting?

If I sat here and counted how many pizza pies we all ate at the end of

this meetup, that probably wouldn't bother anyone. But if I started

counting the number of pieces each of you ate, individually, you would

probably ask me to stop.

There is sort of an ethical issue with considering such data as "given".

Did you "give" me did that data? Or did I "take" it from you? Who's was

it anyways?

|

|

People who sometimes like to use the word 'capta' instead when referring

to this kind of data. It comes from the same root as capture and captive.

|

|

Another term you might be familiar with is 'Personally Identifiable

Information'. This is any data specific to one person or which can be

used to identify a given person.

For the purposes of this talk, let's assume I'm talking about all data

that you generate, or which is about you.

|

|

We're going to start in Germany, which might not be the first place you

think of as the birthplace of data protection. But Germany was an

interesting place after World War II.

|

|

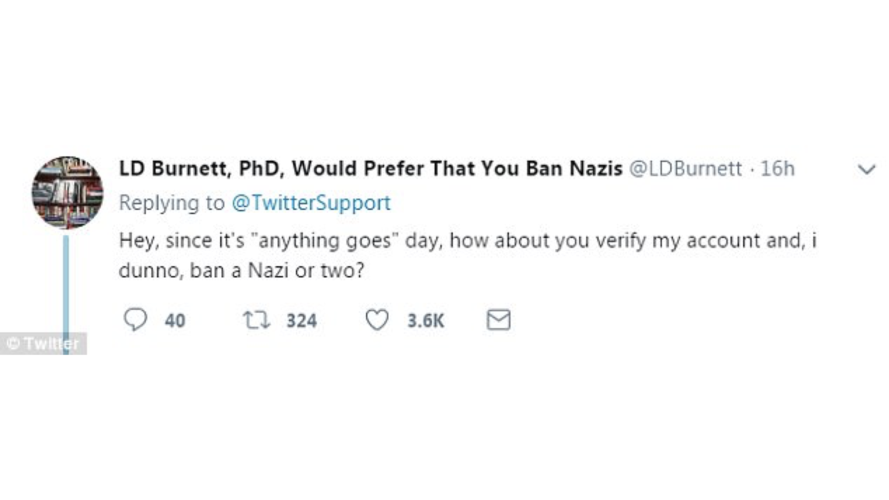

It was kind of like Twitter a few months ago. Many citizens were having a

strong reaction to their previous govenment, and wanted to ensure that a

potential dictator would never again have the chance to come into power

in the country.

|

|

However, you can't just pass a law that says "No Hitlers", so instead,

they passed the Basic Law, which had two key tenets.

|

|

First, a person's individual dignity must be respected and protected

under all circumstances.

|

|

And second, that each person had the right to "freely develop their

personality" (as long as it doesn't injure the rights of others).

|

|

You mind find "personality" to be an interesting choice of words here.

This is because in German, there is not really a direct translation for

the word 'privacy'. Instead, they talk about the "Rights of the

Personality".

|

|

Besides these concerns about dictators, there were some other issues that

Germans in the '50s and '60s were becoming increasingly worried about.

One was nuclear power. Scary, scary nuclear power.

|

|

Another was pollution, much like we are today.

|

|

And the third was data privacy.

All of these have something in common: They all concern the appropriate

use of technological developments. Are we using this new technology in

the 'right' way? There are so many complex and interconnected parts to

concepts like nuclear power, an individual cannot grasp all the issues.

For data privacy specifically, this concern comes from two places: the

increasing use of computers, but also from their country's history. How

did the nazis know who was jewish? Census records, tax returns, synagogue

membership lists. All seemingly harmless data they had let their

govenment collect on them.

|

|

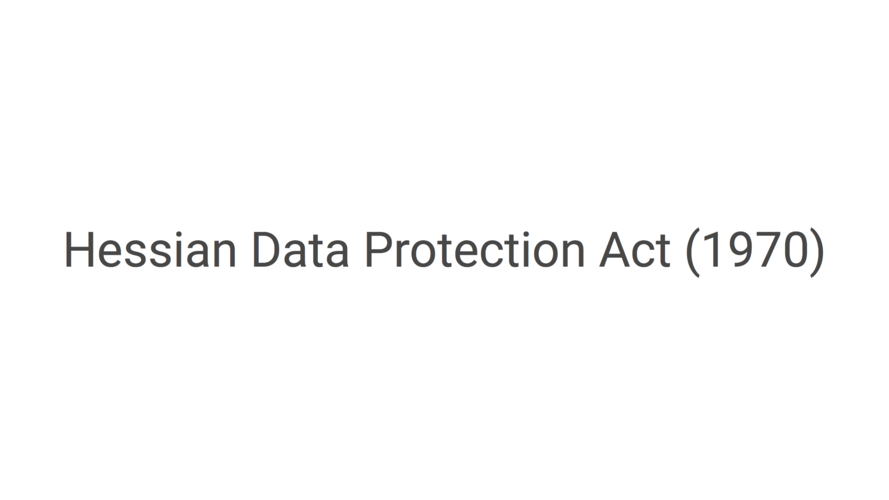

So in 1970, the German state of Hesse passed the Hessian Data Protection

Act. This was more legislation on top of the Basic Law, and the name is

a bit of a misnomer, because it's goal wasn't to protect the data, but to

protect the people whose data are being processed.

|

|

You'll notice that I use the word "processed" a lot when talking about

data in the context of Germany. This is because these laws are only

focused on what could be done ex ante with the data after it was

collected. They are not concerned with how it was collected or stored.

Again, this is a reaction to Germany's history.

|

|

The other limitiation of this law is that it only applies to the

processing of personal data in the public sector. Private companies could

still do whatever they want -- it's governments you have to look out for.

|

|

This law also called for a new position in the state govenment, who would

be in charge of overseeing violations of the Data Protection Act.

Ironically the first commissioner was somewhat of a dictator himself, and

held the post for 16 years.

|

|

This was widely considered the first data protection act, ever. And while

you might think this law seems somewhat primitive, because it's only

focused on uses of the data, and has nothing about encryption, breaches,

etc...

|

|

This was 1970, and this, the Enigma Machine, is the best thing we had in

terms of encryption at the end of WW2.

It wasn't until 1975 that we got the first standard for encryption (DES),

so this is actually pretty good.

|

|

Meanwhile, over in Sweden, they had a completely different set of

circumstances that were leading up to similar data protection laws.

The Swedish government was adopting the use of computers much earlier

than most other countries. The country had a small population, a high

standard of living and high income. And they could forsee usefulness of

automation and computing.

|

|

However there was a downside to all this fast adoption of computers.

Sweden at the time was considered a 'paradise for registers'. The

govenment had vast amounts of information about it's citizens It was said

that the average adult would appear in one hundred data systems, as many

as two hundred if you were married!

This might not seem like much to us. You probably have one hundred apps

on your smartphone alone, so one hundred data systems seems reasonable.

But this is the 1970s!

That much information stored on it citizens alone could be bad (as we've

seen with Germany). But there was another reason why it was becoming

problematic.

|

|

In Swedish law at the time, there was already a strong notion of "the

right of public access", which as early as the Swedish Constitution

mostly meant right of the public to be present at court hearings.

|

|

However in 1949 the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act was passed, which

gave the press the right to government information. Generally, this meant

that there was public access to official records, which is great if

you're a journalist: You're working on a lead, you need to know some

details, you go down to city hall, they pull some files on the person and

they make you a copy.

However, when these records are put in data systems on computers, private

entities would be able to gain vast amounts of information on citizens

with very little effort.

|

|

So in 1973 they passed the very first national data protection act, the

Swedish Data Act.

|

|

This act had three main tenets. The first was the right to get your data,

which is a holdover from previous laws.

|

|

Second was the right to recieve compensation if something bad has

happened to you because some data on you was wrong.

The Swedes, in all their perfectionism, wanted to make sure that all

their data was perfectly accurate.

|

|

And finally, it formally criminalized 'data intrusion'.

|

|

In the law, this literally meant breaking into the offices where the data

lived, and physically stealing it.

The Swedes were smart, but they weren't able to predict the Internet.

|

|

Back in Germany, since since the Hessian law was enacted, other states

were working on similar laws. Based on Sweden, it was determined that

they needed a national law as well.

|

|

So in 1977, Germany passed the German Federal Data Protection Act, which

took all the state's laws, and combined them into a single federal law.

|

|

This law had three goals, which had distinct echos of the previous

Hession law. First, it prevented the 'misuse' of data.

|

|

Second, it wanted to prevent harm to any citizen's personal interests.

|

|

And finally, it actually created a regulating body which would give out

permits for people to do data processing.

This means that can't just collect data and then decide what to do with

it later, you have to go and get approval every time you want to do

something different with it.

|

|

Over in the UK, people were also having similar concerns, and decided

they wanted some data protection too.

|

|

In 1984, the UK Data Protection Act was passed, but only after much

reluctance and dragging of feet by the British government, the archetypal

'nanny state'.

|

|

In fact, one early commission actually found that there was no need for

data protection at all!

As you might not be surprised to discover, this law was widely

criticised.

|

|

But in 1985, the UK joined the European Communities, which was a

precursor to the European Union, and they were working on their own

policies.

Just look how optimistic that flag is! So bright and shiny and sunny.

|

|

And indeed, in 1995, they got the EU Data Protection Directive.

|

|

Generally, this was about having a baseline respect for privacy (subject

to certain restrictions).

But more specifically, it had seven key recommendations.

|

|

The first is notice. Data subjects should be given notice when their data

is being collected.

|

|

Next is purpose. Data should only be used for the purpose stated and not

for any other purposes.

|

|

Third is consent, and this is the first time we're really talking about

consent at all with regards to data protection. It means data should not

be disclosed without the data subject’s explicit agreement.

|

|

Fourth is security, which is incredibly broad and mostly means that

collected data should be kept secure from any potential abuses.

|

|

Fifth is disclosure. This is not about breach disclosure, or

vulnerability disclosure, but just that data subjects should be informed

as to who is collecting their data.

|

|

Sixth is access and clearly a holdover from previous Swedish laws: data

subjects should be allowed to access their data and make corrections to

any inaccurate data.

|

|

And finally accountability. Data subjects should have a method available

to them to hold data collectors accountable for not following the above

principles.

|

|

This is awesome! Except... it's a directive. Which means it's not a law,

and thus it's non-binding. It's just a suggestion, recommendation or

'best practices' and nobody actually has to follow it.

So of course, nobody does.

|

|

We're well into the 90's now, not so far in the past.

|

|

Notice anybody missing from this long history of data protection laws?

|

|

How about the good ol' US of A?

Can anyone name the major national data protection law we have here in

the United States?

At this point, somebody yells out "The Patriot Act!", which

I point out is pretty much the exact opposite of a

national data protection law.

|

|

Some folks might say the Fourth Amendment. It's goal is to protect us

from unreasonable search & seizures.

|

|

And in fact, the closest we've come to challenging the massive

wiretapping and metadata program by the US government is when a district

court ruled that it "probably violated the 4th amendment".

|

|

However, in the Supreme Court case ACLU v. Clapper it was

determined that the global telephone data-gathering system is needed to

thwart potential terrorist attacks, that it can only work if everyone's

calls are included, that Congress legally set up the program and that it

does not violate anyone's constitutional rights.

As it turns out, wiretapping every US citizen doesn't actually constitute

unreasonable search and seizure.

|

|

So, yeah, we don't really have a national data protection law.

|

|

Oh, but we do have the Video Rental Protection Act from 1988!

This law prevents the wrongful disclosure of video tape rental or sale

records. So that's cool.

Don't get me wrong, we actually have a lot of laws like this, and they

aren't really bad laws at all. Netflix was actually recently prosecuted

under this law for sharing it's data with Facebook.

|

|

But the problem is that while strong, all of these address a very small,

specific area of data protection. HIPPA is just for health records. Fair

Credit Reporting Act is just so that you can correct your credit history

if it's wrong. (Doesn't say anything about what happens if it's breached,

though). CAN-SPAM literally made spam email illegal.

|

|

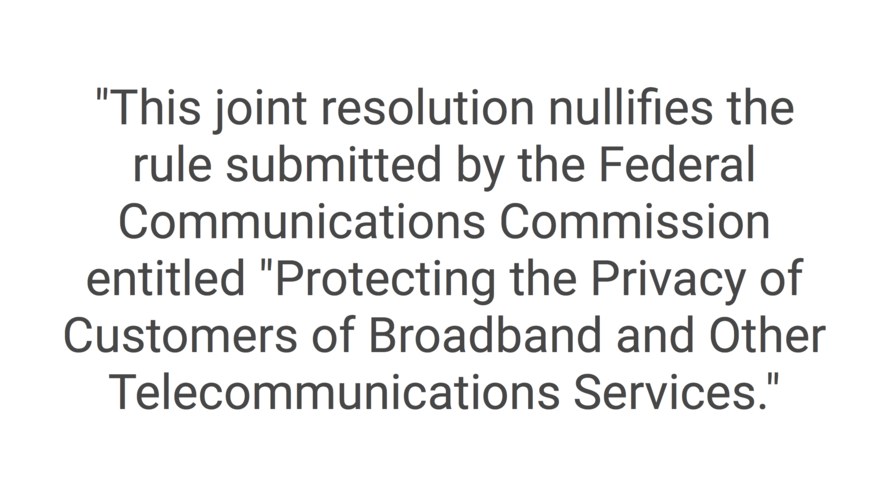

The other problem is things like Senate Joint Resolution 34, which was

recently signed into law by... somebody...

|

|

TLDR; ISPs can sell your browsing history again!

|

|

So maybe you're thinking "Everything is terrible."

Well, yeah, maybe, if you live in the US.

|

|

But remember that beautiful, shining, optimistic EU flag?

If tomorrow you decide you want to move to Sweden (and I don't blame you

if you do), you'd be about to get a brand, new...

|

|

EU General Data Protection Regulation! Or "GDPR".

|

|

This regulation has an incredibly broad scope. It applies to you if the

data controller (person holding data), data processor (person doing

something with data), or data subject is based in the EU.

This means that if you're an American company that has customers in the

EU, you must comply!

|

|

The regulation has the same overarching rules for all member states, and

they might seem somewhat familiar at this point.

|

|

First, the Right of Erasure. This is commonly called "The Right To Be

Forgotten," which is way more poetic.

This means that if someone has data about you, you have the right to tell

them to erase it -- forever!

|

|

The Right of Access means that you, as an EU citizen, have the right to

get a copy of all the data a company has on you.

|

|

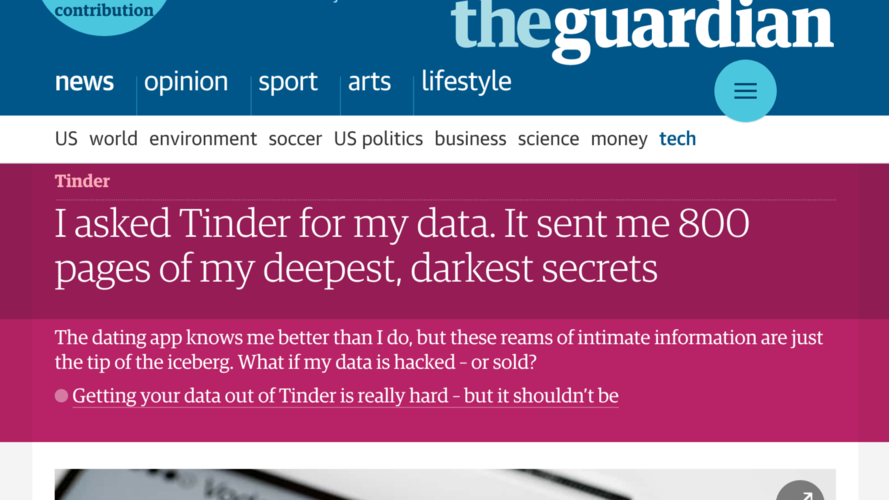

This has led to some pretty wild newspaper articles where some journalist

calls up Tinder and gets their mind blown when they realize for the first

time that tech companies actually store everything you do.

And yeah, what if it's hacked or sold?

|

|

If there's a data breach, it must be must be reported within 72 hours.

Not within a year, like Uber recently fessed up to. Not within a month,

like Equifax.

|

|

Furthermore, if there has been a breach, and the data got sold or

whatever, for any person that has suffered material or

non-material damage shall have the right to recieve monetary

compensation.

This is a big deal! Here in the US, if we all wanted to get together and

sue some company for some crime against us, we could hire a lawyer,

create a class-action lawsuit, and take them to court. But there's no

such thing as a class-action lawsuit in the EU, so before this law, if

you suffered some damages from a company, there wasn't a whole lot you

could do.

|

|

Pseudoanonymisation means that it should not be possible to attributed

some piece of data to a specific data subject without the use of

'additional information'.

So really this just means 'use encryption'.

|

|

Here's consent again. This means that data collectors must be explicit

about what is being gathered and what it is being used for. And, they

can only use the data for the consented purposes!

This is why when you visit the Guardian or other websites based in

Europe, they show you a huge banner that says "THIS SITE USES COOKIES"

and you have to agree to letting them use cookies. That's consent!

|

|

The other interesting thing this regulation does is create a required

role at any company that processes or stores large amounts of data. This

person should have expert knowledge of data protection law and practices

should assist the controller or processor to monitor internal compliance.

|

|

And the best part about this regulation: it's a law! Which means that you

can get sanctioned if you don't comply.

Sanctions range from a warning (in cases of first and non-intentional

noncomplance), to regular periodic data protection audits, to fine of 20M

euros or 4% of annual worldwide revenue, whichever is greater.

To put that number in perspective, Facebook had 27 billion dollars in

revenue last year, so their fine would be more than a billion dollars.

|

|

And the law goes into effect this year!

|

|

So that's the present, and just right around the corner. Let's talk about

my three main predictions for data protection in the future.

|

|

First, GDPR compliance is going to be a big deal. Just like 'HIPPA

compliance', but way more complex. It will be (and has already become) an

industry.

|

|

Second, someone's gonna get sanctioned. Likely one of the big tech

companies, because not only do the regulators need to make an example out

of somebody, but they're going to be relying on the fines to fund the

work required to enforce the regulation.

|

|

And finally, I don't expect anything in the US to get better in the next,

oh... three years or so. Just a hunch.

Instead, expect further dismantling of privacy laws and regulations.

|

|

Insert way too many questions to include here.

|

|

One last thing: I'm not trying to hate on all the companies I used as

examples here. I'm sure those companies already take data protection very

seriously and there's a lot of smart people working hard to ensure that

it's used properly and never breached.

However, we live in an age where the ability to generate data about

oneself and the capacity of others to collect it is enormous. It might

not come as a surpise to any of you that Tinder has so much data on it's

users, but for the majority of them, they simply do not know.

We need to make sure on their behalf, and for our own sake, that this

data is being protected, used responsibly, and that it will not and

cannot endanger the people from which it has been taken.

Thanks!

|