|

This talk is about the principles of designing software for the "long

now", and my experiences working with "long software".

|

|

In a former life, prior to being a professional software engineer, I was

a woodworker. I made custom furniture and cabinetry, finishwork and

millwork.

One day I was working on a window very much like this one. I was taking

the old window out, repairing the framing around it, putting a new one in

place, and doing all the finish work.

This was in an old house, in Philadelphia, and I realised as I was

removing the old window that it had probably been there for about a

hundred years.

I also realised that if I did a really good job installing the new

window, it would probably be there for about a hundred years as well.

When I started working in technology, I really struggled with the

ephemerality of my work. We often build physical objects to exist for a

hundred years or more, but we don't really do this with software.

|

|

This is Danny Hillis. Danny spent his lifetime building supercomputers,

and while Danny is still alive, there are probably more computers of his

in museums today than are still running.

I'm sure that Danny also has struggled with the ephemerality of the work

that he has done as well.

In the nineties, as we got closer and closer to the new millenium, Danny

began to notice something about how we were thinking about the future.

As we got closer to the year 2000, we, as a society, were becoming more

and more fixated on a smaller and smaller distance into the future. We

were thinking a lot about what would happen in the year 2000, but not

much about what would happen after that.

Danny came up with an idea, with the goal of making us think about the

future on a longer time scale.

|

|

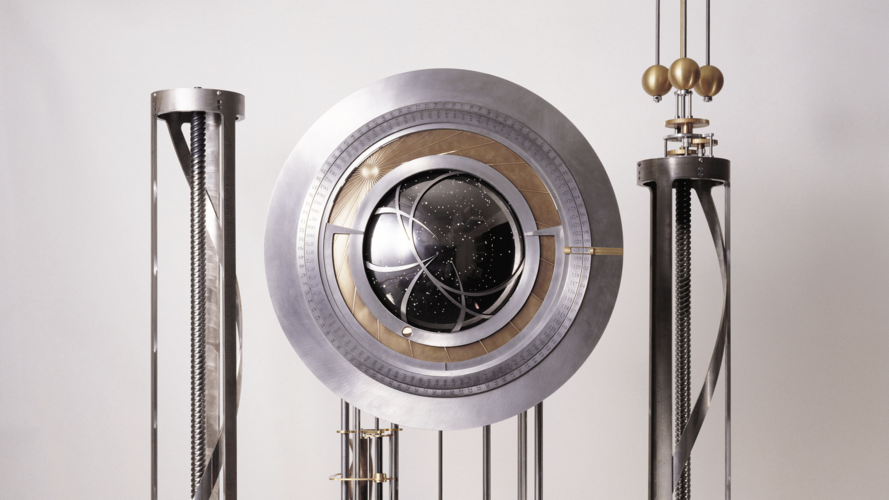

His idea was to build a clock. This clock would only tick once a year,

and once every thousand years, a cuckoo would come out. He wanted this to

happen, accurately, for the next ten thousand years.

He chose ten thousand years because this is just within the limits of

plausibility. We have found human artifacts that are approximately that

old, but nothing so complex, and nothing specifically cared for for that

long.

Danny was able to make his dream a reality.

|

|

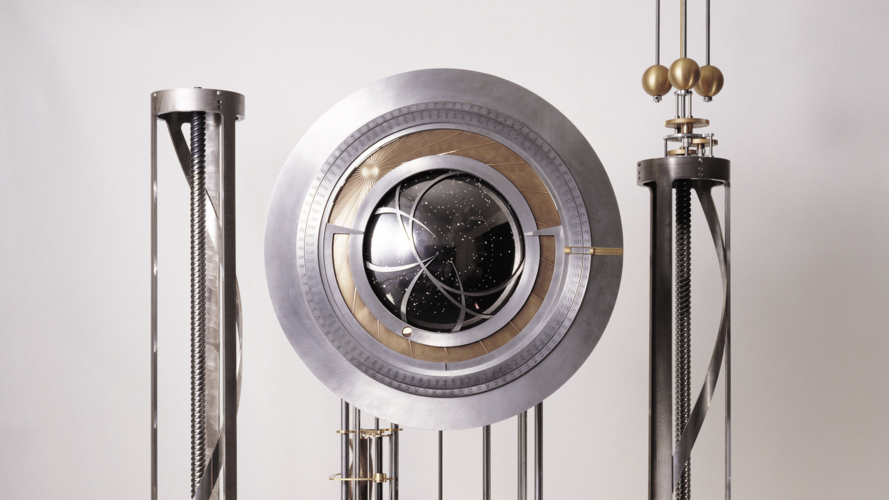

This is the Clock of the Long Now. It was finished January 31st, 1999,

just in time to ring in the new year.

When Danny was designing and building this clock, he found five key

design principles which he felt were most important to making the idea a

success.

|

|

The first of these principles was longevity.

Aside from just being accurate for ten thousand years, the clock also

needed physical longevity -- safe from rust, from flooding, from

potential looters if it was made out of valuable materials.

|

|

The second principle was maintainability. This clock needs to be

maintainable by future generations, with minimal tools, possibly even

with bronze-age tools.

This is especially important when designing how to power the clock. It

immediately rules out power sources like nuclear energy, which aren't

readily maintainable, especially with bronze-age tools.

Instead, the clock is hand-wound, and in the event that no one is around

to wind it for a very long time, it can capture energy from the changes

in temperature between day and night.

|

|

The third principle is transparency. The clock needs to be

understandable by it's maintainers, without stopping.

This is especially important considering that it's original creators will

be long gone.

|

|

The fourth principle is evolvability. The clock needs to be able to be

improved over time.

For example, the rotation of the earth is slowing at a noticeable, but

unpredictable rate. It should be possible to adjust the clock to

compensate for the changing length of day, without stopping the clock.

|

|

The final principle is scalability. This means that it should be possible

to build working scale prototypes of the clock, and then scale those up

for the final version.

|

|

In fact, when I told you before that this was the Clock of the Long Now,

it was not quite accurate. This is actually a scale prototype of the

clock.

|

|

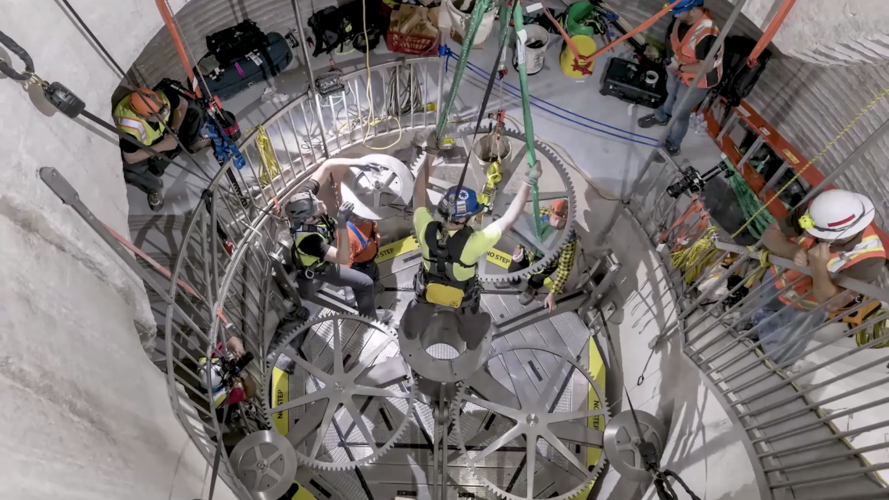

This is the size of the actual clock, with gears as large as humans...

|

|

...a massive pendulum,

|

|

...and all inside a 500-foot deep shaft inside a mountain.

And even this is not the final version of the clock! This is just a 1:1

prototype, currently installed in West Texas.

|

|

The final version of this clock will be sunk into this mountain, Mount

Washington, in Nevada.

When you're building a giant clock inside of mountain, your biggest

concerns are things like earthquakes, the changing rotational speed of

the earth, et cetera. These are geologic, planetary concerns!

We don't ever design software to exist at this scale, let alone a

one-hundred year scale.

|

|

If I were able to run git blame on every line of code necessary

to make your laptop run, what do you think would be the oldest unchanged

line? Ten years? Twenty? Thirty?

Here's a better question: what is something that you've created,

that's still in use? If it's code, how long will it be used? If it's

documentation, how long will it be relevant? If it's a technical talk,

when is the last time someone will watch it?

As technologists, we don't really want to think about this. Not only does

it make us think of our own mortality, but when we're constantly trying

to move fast and break things, why bother?

|

|

I think the closest I've come is the work I've done on the Python Package

Index. PyPI, for those unaware, is the canonical repository for Python

packages, and I'm a contributor, maintainer and administrator of the

project.

|

|

PyPI is what picks up the phone at the other end of the line when you

pip install something. It's one of the oldest language-specific

package repositories, and like in most programming languages, this

centralized repository didn't exist when Python was first created.

There's an apocryphal joke within the Python packaging community that

Guido van Rossum, the creator of Python, has never felt the need for

something like PyPI, because any Python code that he wanted to use that

didn't come with Python, he could just put it in the standard library.

This isn't quite true, but the early contributors to Python really didn't

see a need for a centralized package repository. They saw packaging as a

solved problem, and couldn't imagine Python being used on a platform that

didn't have a platform-level package manager

|

|

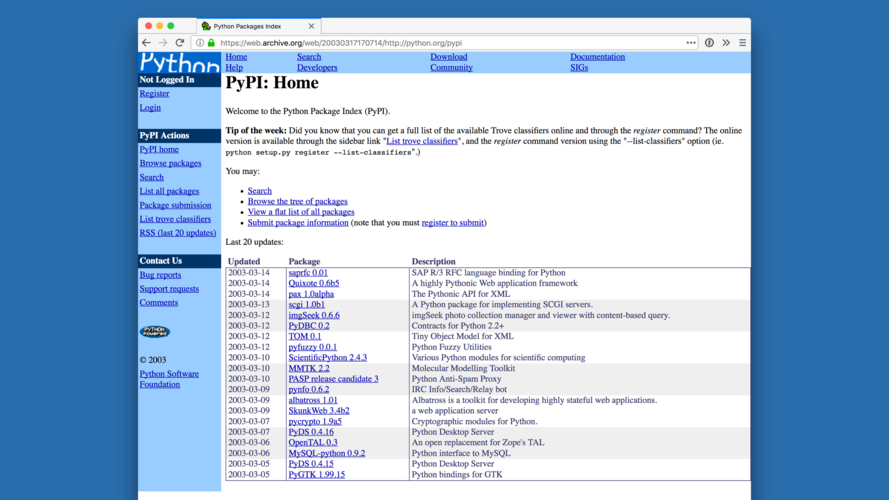

As it turns out, developers love to write software on platforms

without their own package managers. So in 2003 PyPI was created.

It was originally just a prototype. It didn't even host any distributions

itself, it just linked to files hosted elsewhere. But it still worked

pretty well.

|

|

And as we all know, any sufficiently advanced prototype is

indistinguishable from production software. So it quickly became

"production software".

|

|

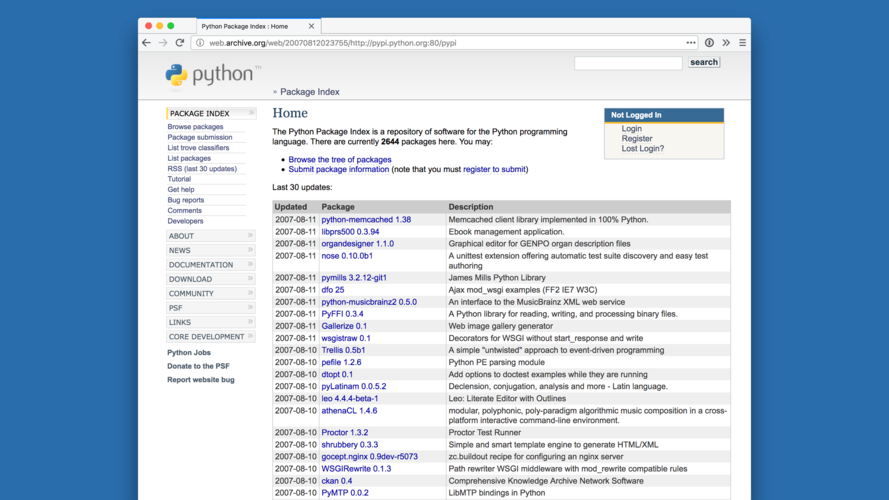

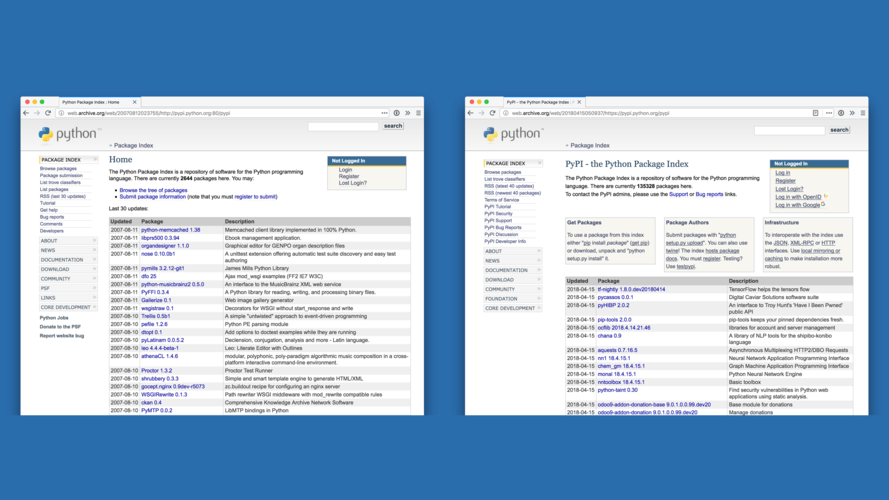

And it was pretty successful! This is PyPI in 2007, four years later. You

can see it's improved a bit.

|

|

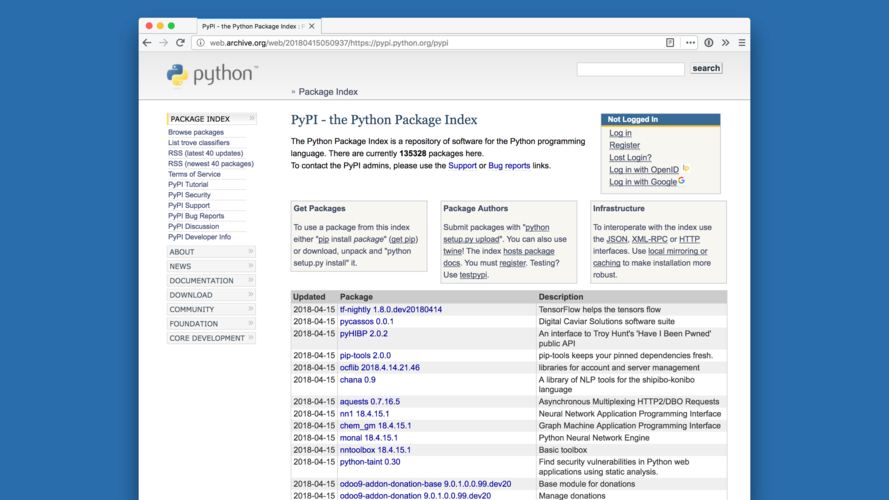

But this is PyPI in 2018.

|

|

I'll put these screenshots side by side. There's eleven years between

these two images, but PyPI still looks exactly the same -- not like a

modern website at all.

|

|

It's a little unfair to compare these visually, because one thing that

you can't see in these images is that in these eleven years, PyPI went

from hosting about three thousand packages, to more than one hundred and

forty thousand.

It went from "a" place to put Python code, to "the" place. This means

that there was a lot of work done behind the scenes to keep this

prototype working at this larger scale.

|

|

The other thing worth mentioning with regards to why PyPI didn't change

much is that by it's very nature, it has a bit of a chicken-and-egg

problem.

When PyPI was first created, none of the packages that it currently hosts

were available, including modern web frameworks, testing frameworks, etc.

|

|

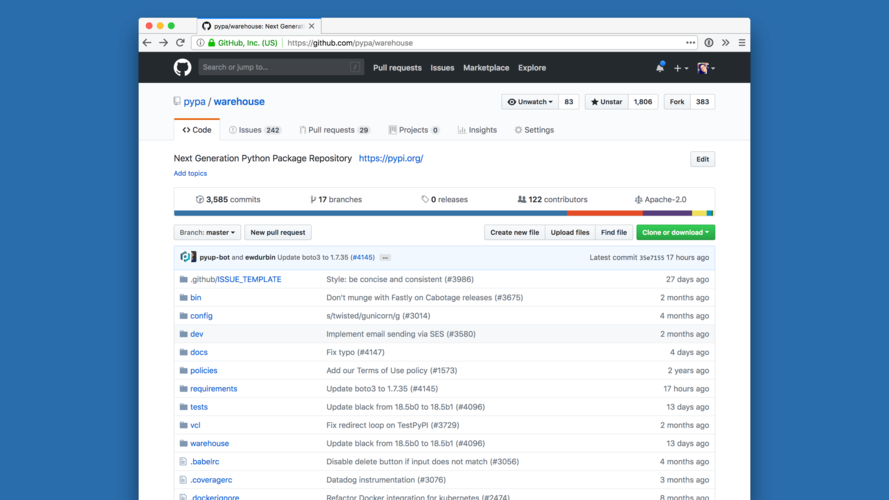

So in 2015, some folks decided to rewrite PyPI from scratch. The project

officially started in 2015, and I joined it in early 2016.

And while we were making pretty good progress, it was an entirely

volunteer-driven project... so it seemed like it might never actually be

finished.

|

|

Thus, in November of last year, we applied for a Mozilla Open Source

Support grant for myself, an infrastructure engineer, a designer and

project manager to work on this rewrite full-time.

|

|

And, six months later in April, we launched! The project became the

canonical PyPI, and we phased out the fifteen-year old legacy codebase.

|

|

We did what we had told Mozilla we wanted to do: finish and launch the

rewrite. But we had an ulterior motive: to ultimately turn PyPI into

software for the long now.

Because as it turns out, the same principles for designing a ten-thousand

year clock are generally good principles for designing anything to last a

long time.

|

|

First, longevity. It should always be possible to pip install

the first module ever uploaded to PyPI. And, it should still install the

same code.

|

|

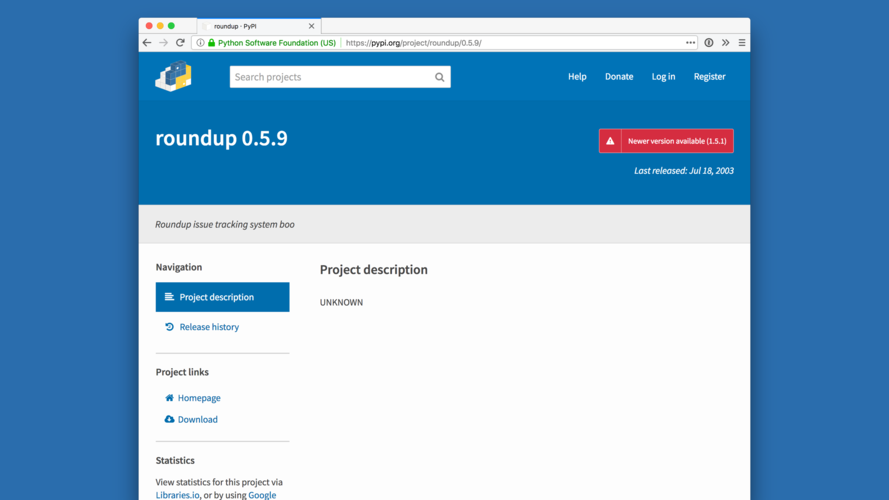

This is the first project ever uploaded to PyPI. It's not that

interesting, aside from the fact that it's fifteen years old and you can

still install it with modern tools, thanks to painstaking work to

maintain backwards compatibility.

|

|

Second is maintainability. Since PyPI is a volunteer-driven project, this

means that we must design it in a way to require as little maintenance as

possible.

I don't want it to require a lot of my time, and thus I also want it to

be maintainable by people that aren't me (and I don't want it to take up

a lot of their time, either).

|

|

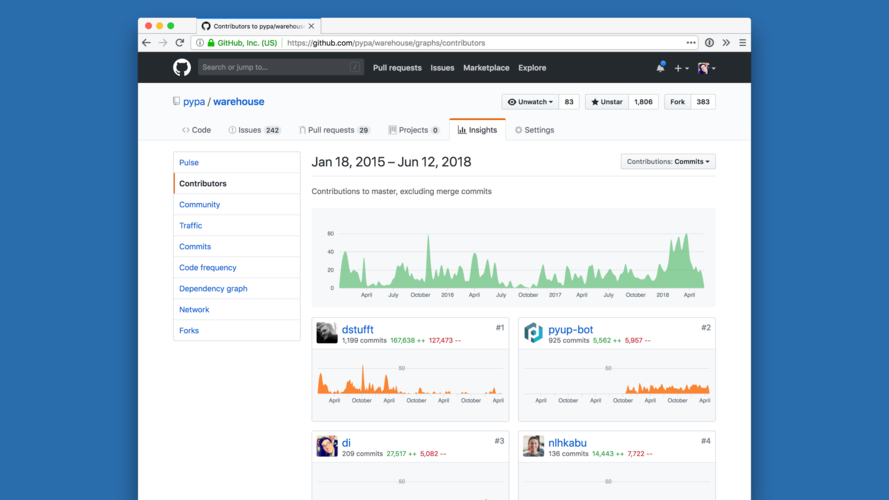

This means that during the course of the grant, we also spent a lot of

time working on building community around the project, acquiring new

contributors and maintainers.

|

|

Third is transparency. It's easy to say "Oh! It's an open-source project, therefore it's transparent".

And while this does go a long way towards being transparent, it's not

enough. Adding documentation helps, but often docs are too focused on the

"how" something works, or "how" to use it.

For a project like this to be truly transparent, a new person approaching

it needs to be able to understand the thoughts, discussions and decisions

which lead to understanding "why" the project is designed the way it is.

|

|

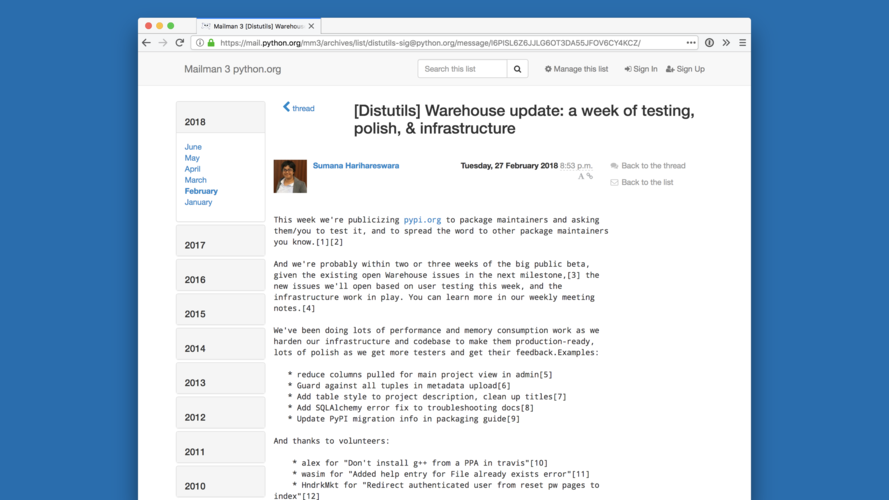

For us, this meant that we minimized any backchannel communication as

much as possible, and recorded everything, including our meetings, and

published the records in multiple places where they would be permanently

archived.

I also spent a lot of time thinking about how I responded to users on

GitHub, making sure that not only was I answering their immediate

question, but providing enough context and background for any future

visitors to that issue or pull request, for them to understand it as

well.

|

|

Fourth is evolvability. There's a number of ways which we've made PyPI

more "evolvable".

|

|

The first is tests. PyPI currently has one hundred percent test coverage.

When I tell people this, they think I'm nuts, that this is possibly

overkill. Which would definitely be true if PyPI were not designed to

last so much longer than most software.

Having 100% coverage allows any contributor to come and propose changes

and not only know if their changes will break things, but also have

confidence that their changes will likely not break things for PyPI's

hundreds of thousands of users.

It also raises the amount of investment a contributor must make to ship a

new feature, which helps prevent us from making changes too quickly that

we might not have thought through fully, or might not want to support for

the next 15 years.

|

|

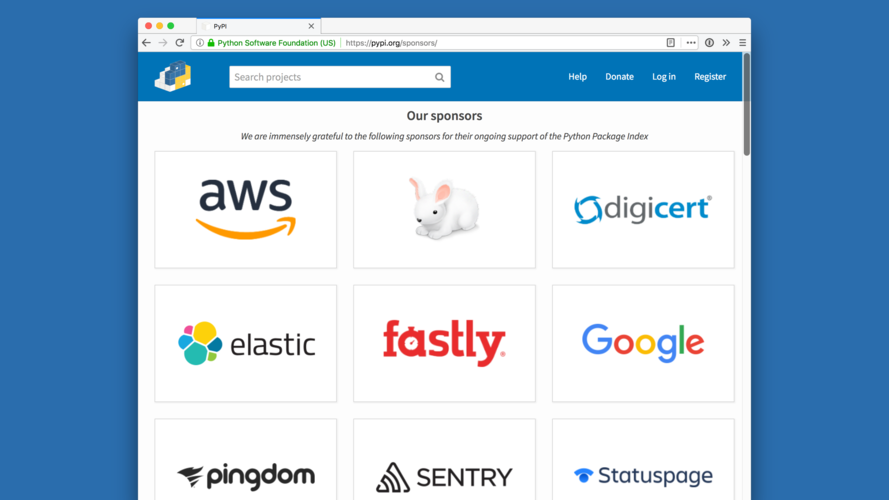

Second is sponsors. PyPI runs entirely on donated infrastructure from our

sponsors.

In order for PyPI to stay running, it needs to be able to evolve in the

event that one of our sponsors goes away for some reason.

By being infrastructure-agnostic and following good software practices by

abstracting away our dependencies on these services as much as possible,

we make it as easy as possible to replace one sponsor with another.

|

|

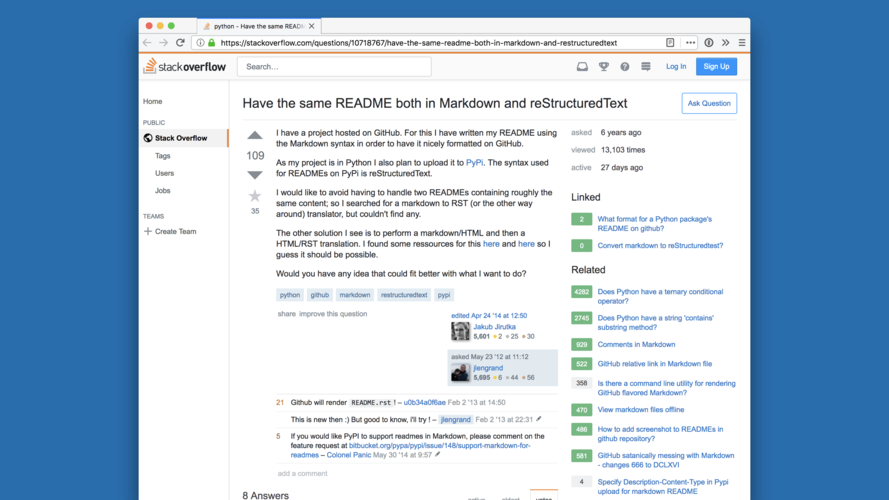

Finally, just having a modern codebase lets us ship the features that

our users want, and spend less time fighting fires.

For example, one of the most oft-requested features for PyPI is the

ability to write the project description in Markdown. We didn't support

this before because when PyPI was first created, Markdown didn't exist,

so it wasn't designed with it in mind, and the lack of modern frameworks

made it more challenging than it should be.

|

|

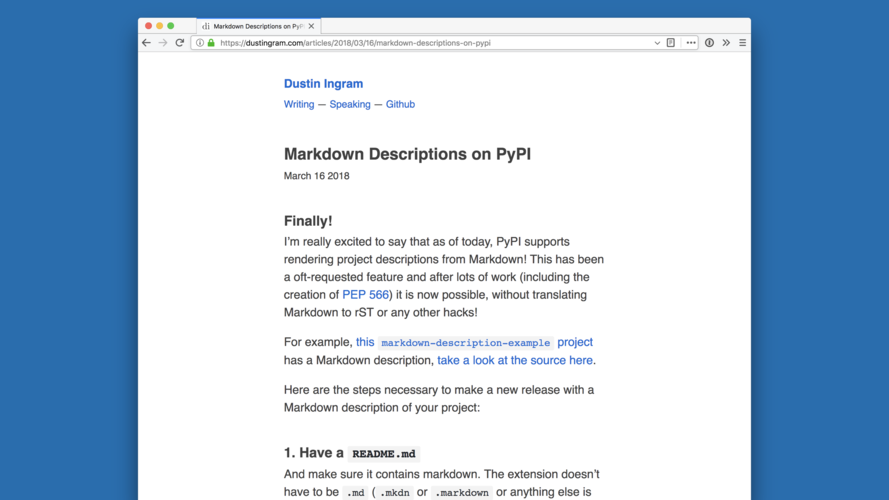

This was the thing I was most excited to do once we had launched...

|

|

...and people loved it. This is a case where evolvability begets

popularity, and thus survivability. If we can't give our users the

features they want, they're going to go elsewhere.

|

|

Finally is scalability. PyPI has definitely had it's prototype, and we've

learned a lot from it.

For us, this is more about scalability in the more traditional sense: Can

PyPI support the growing demands in the next year? In the next decade?

|

|

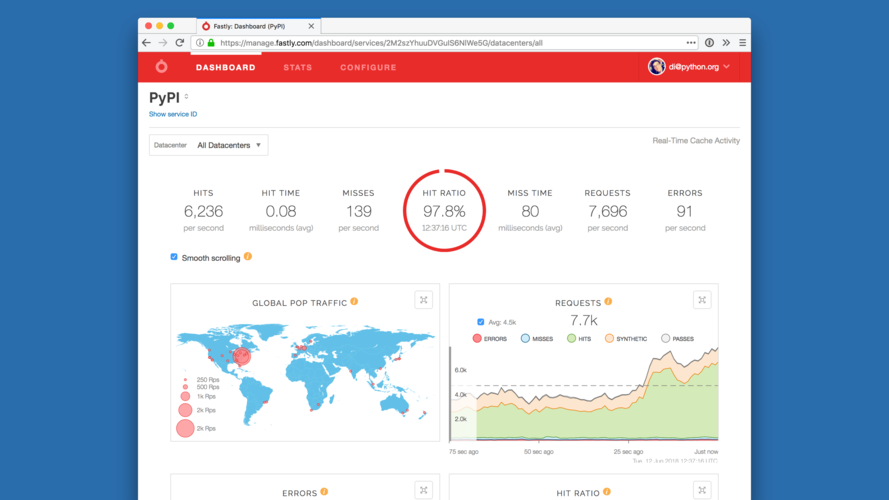

One thing we've done to sure that PyPI can scale: we put it behind a

content distribution network (CDN).

If something on PyPI is going to potentially be viewed more than once, we

put it in the cache. This requires lots of extra logic around when to

invalidate the cache, but it pays off: as a result PyPI currently handles

about two billion requests per day, and serves more than 20 terabytes of

bandwidth -- and can handle an order of magnitude more.

|

|

All this to say: I'm confident that PyPI will not only continue to exist

at least for the next fifteen years, but that it will continue to grow

and evolve, and not stagnate like it's predecessor.

|

|

I often think back to this window at the beginning of the story.

Like the Clock of the Long Now, it helps give me a greater perspective on

what I'm building in a less immediate time frame. It also helps me focus

the work that I'm currently doing on the projects that will have the

greatest impact on the future.

And last I checked, it's still there. 🙂

|

|

Thanks for your time!

|